What I learned from competing against a ConvNet on ImageNet

The results of the 2014 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) were published a few days ago. The New York Times wrote about it too. ILSVRC is one of the largest challenges in Computer Vision and every year teams compete to claim the state-of-the-art performance on the dataset. The challenge is based on a subset of the ImageNet dataset that was first collected by Deng et al. 2009, and has been organized by our lab here at Stanford since 2010. This year, the challenge saw record participation with 50% more participants than last year, and records were shattered with staggering improvements in both classification and detection tasks.

(My personal) ILSVRC 2014 TLDR: 50% more teams. 50% improved classification and detection. ConvNet ensembles all over the place. Google team wins.

Of course there’s much more to it, and all details and takeaways will be discussed at length in Zurich, at the upcoming ECCV 2014 workshop happening on September 12.

Additionally, we just (September 2nd) published an arXiv preprint describing the entire history of ILSVRC and a large amount of associated analysis, check it out on arXiv. This post will zoom in on a portion of the paper that I contributed to (Section 6.4 Human accuracy on large-scale image classification) and describe some of its context.

ILSVRC Classification Task

For the purposes of this post, I would like to focus, in particular, on image classification because this task is the common denominator for many other Computer Vision tasks. The classification task is made up of 1.2 million images in the training set, each labeled with one of 1000 categories that cover a wide variety of objects, animals, scenes, and even some abstract geometric concepts such as “hook”, or “spiral”. The 100,000 test set images are released with the dataset, but the labels are withheld to prevent teams from overfitting on the test set. The teams have to predict 5 (out of 1000) classes and an image is considered to be correct if at least one of the predictions is the ground truth. The test set evaluation is carried out on our end by comparing the predictions to our own set of ground truth labels.

GoogLeNet’s Impressive Performance

I was looking at the results about a week ago and became particularly intrigued by GoogleLeNet’s winning submission for the classification task, which achieved a Hit@5 error rate of only 6.7% on the ILSVRC test set. I was relatively familiar with the scope and difficulty of the classification task: these are unconstrained internet images. They are a jungle of viewpoints, lighting conditions, and variations of all imaginable types. This begged the question: How do humans compare?

There are now several tasks in Computer Vision where the performance of our models is close to human, or even superhuman. Examples of these tasks include face verification, various medical imaging tasks, Chinese character recognition, etc. However, many of these tasks are fairly constrained in that they assume input images from a very particular distribution. For example, face verification models might assume as input only aligned, centered, and normalized images. In many ways, ImageNet is harder since the images come directly from the “jungle of the interwebs”. Is it possible that our models are reaching human performance on such an unconstrained task?

Computing Human Accuracy

In short, I thought that the impressive performance by the winning team would only make sense if it was put in perspective with human accuracy. I was also in the unique position of being able to evaluate it (given that I share office space with ILSVRC organizers), so I set out to quantify the human accuracy and characterize the differences between human predictions with those of the winning model.

Wait, isn’t human accuracy 100%? Thank you, good question. It’s not, because the ILSVRC dataset was not labeled in the same way we are classifying it here. For example, to collect the images for the class “Border Terrier” the organizers searched the query on internet and retrieved a large collection of images. These were then filtered a bit with humans by asking them a binary “Is this a Border Terrier or not?”. Whatever made it through became the “Border Terrier” class, and similar for all the other 1000 images. Therefore, the data was not collected in a discriminative but a binary manner, and is also subject to mistakes and inaccuracies. Some images can sometimes also contain multiple of the ILSVRC classes, etc.

CIFAR-10 digression. It’s fun to note that about 4 years ago I performed a similar (but much quicker and less detailed) human classification accuracy analysis on CIFAR-10. This was back when the state of the art was at 77% by Adam Coates, and my own accuracy turned out to be 94%. I think the best ConvNets now get about 92%. The post about that can be found here. I never imagined I’d be doing the same for ImageNet a few years down the road :)

There’s one issue to clarify on. You may ask: But wait, the ImageNet test set labels were obtained from humans in the first place. Why go about re-labeling it all over again? Isn’t human performance 0% by definition? Kind of, but not really. It is important to keep in mind that ImageNet was annotated as a binary ask. For example, to collect images of the dog class “Kelpie”, the query was submitted to search engines and then humans on Amazon Mechanical Turk were used for the binary task of filtering out the noise. The ILSVRC classification task, on the other hand, is 1000-way classification. It’s not a binary task such as the one used to collect the data.

Labeling Interface

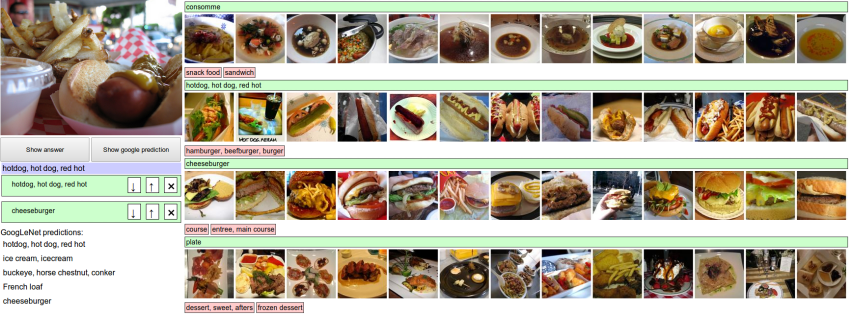

I developed a labeling interface that would help us evaluate the human performance. It looked similar to, but not identical, to the screenshot below:

The interface consisted of the test image on the left, and 1000 classes listed on the right. Each class was followed by 13 example images from the training set so that the categories were easier for a human to scan visually. The categories were also sorted in the topological order of the ImageNet hierarchy, which places semantically similar concepts nearby in the list. For example, all motor vehicle-related classes are arranged contiguously in the list. Finally, the interface is web-based so it is easy to naturally scroll through the classes, or search for them by text.

Try it out! I’m making the the labeling interface available to everyone so that you can also try labeling ILSVRC yourselves and draw your own conclusions. There are a few modifications in this version from the one we used to collect the data. I added two buttons (Show answer, and Show google prediction), and of course, the images shown in this version are the validation images, not the test set images. The GoogLeNet validation set predictions were graciously provided by the Google team.

Roadblocks along the way

It was hard. As I beta-tested the interface, the task of labeling images with 5 out of 1000 categories quickly turned out to be extremely challenging, even for some friends in the lab who have been working on ILSVRC and its classes for a while. First we thought we would put it up on AMT. Then we thought we could recruit paid undergrads. Then I organized a labeling party of intense labeling effort only among the (expert labelers) in our lab. Then I developed a modified interface that used GoogLeNet predictions to prune the number of categories from 1000 to only about 100. It was still too hard - people kept missing categories and getting up to ranges of 13-15% error rates. In the end I realized that to get anywhere competitively close to GoogLeNet, it was most efficient if I sat down and went through the painfully long training process and the subsequent careful annotation process myself.

It took a while. I ended up training on 500 validation images and then switched to the test set of 1500 images. The labeling happened at a rate of about 1 per minute, but this decreased over time. I only enjoyed the first ~200, and the rest I only did #forscience. (In the end we convinced one more expert labeler to spend a few hours on the annotations, but they only got up to 280 images, with less training, and only got to about 12%). The labeling time distribution was strongly bimodal: Some images are easily recognized, while some images (such as those of fine-grained breeds of dogs, birds, or monkeys) can require multiple minutes of concentrated effort. I became very good at identifying breeds of dogs.

It was worth it. Based on the sample of images I worked on, the GoogLeNet classification error turned out to be 6.8% (the error on the full test set of 100,000 images is 6.7%). My own error in the end turned out to be 5.1%, approximately 1.7% better. If you crunch through the statistical significance calculations (i.e. comparing the two proportions with a Z-test) under the null hypothesis of them being equal, you get a one-sided p-value of 0.022. In other words, the result is statistically significant based on a relatively commonly used threshold of 0.05. Lastly, I found the experience to be quite educational: After seeing so many images, issues, and ConvNet predictions you start to develop a really good model of the failure modes.

My error turned out to be 5.1%, compared to GoogLeNet error of 6.8%. Still a bit of a gap to close (and more).

Analysis of errors

We inspected both human and GoogLeNet errors to gain an understanding of common error types and how they compare. The analysis and insights below were derived specifically from GoogLeNet predictions, but I suspect that many of the same errors may be present in other methods. Let me copy paste the analysis from our ILSVRC paper:

Types of error that both GoogLeNet human are susceptible to:

-

Multiple objects. Both GoogLeNet and humans struggle with images that contain multiple ILSVRC classes (usually many more than five), with little indication of which object is the focus of the image. This error is only present in the Classification setting, since every image is constrained to have exactly one correct label. In total, we attribute 24 (24%) of GoogLeNet errors and 12 (16%) of human errors to this category. It is worth noting that humans can have a slight advantage in this error type, since it can sometimes be easy to identify the most salient object in the image.

-

Incorrect annotations. We found that approximately 5 out of 1500 images (0.3%) were incorrectly annotated in the ground truth. This introduces an approximately equal number of errors for both humans and GoogLeNet.

Types of error that GoogLeNet is more susceptible to than human:

-

Object small or thin. GoogLeNet struggles with recognizing objects that are very small or thin in the image, even if that object is the only object present. Examples of this include an image of a standing person wearing sunglasses, a person holding a quill in their hand, or a small ant on a stem of a flower. We estimate that approximately 22 (21%) of GoogLeNet errors fall into this category, while none of the human errors do. In other words, in our sample of images, no image was mislabeled by a human because they were unable to identify a very small or thin object. This discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that a human can very effectively leverage context and affordances to accurately infer the identity of small objects (for example, a few barely visible feathers near person’s hand as very likely belonging to a mostly occluded quill).

-

Image filters. Many people enhance their photos with filters that distort the contrast and color distributions of the image. We found that 13 (13%) of the images that GoogLeNet incorrectly classified contained a filter. Thus, we posit that GoogLeNet is not very robust to these distortions. In comparison, only one image among the human errors contained a filter, but we do not attribute the source of the error to the filter.

-

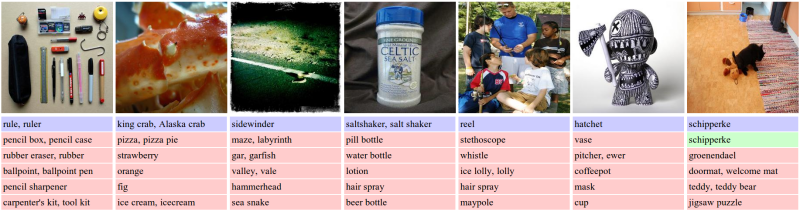

Abstract representations. We found that GoogLeNet struggles with images that depict objects of interest in an abstract form, such as 3D-rendered images, paintings, sketches, plush toys, or statues. An example is the abstract shape of a bow drawn with a light source in night photography, a 3D-rendered robotic scorpion, or a shadow on the ground, of a child on a swing. We attribute approximately 6 (6%) of GoogLeNet errors to this type of error and believe that humans are significantly more robust, with no such errors seen in our sample.

-

Miscellaneous sources. Additional sources of error that occur relatively infrequently include extreme closeups of parts of an object, unconventional viewpoints such as a rotated image, images that can significantly benefit from the ability to read text (e.g. a featureless container identifying itself as “face powder”), objects with heavy occlusions, and images that depict a collage of multiple images. In general, we found that humans are more robust to all of these types of error.

Types of error that human is more susceptible to than GoogLeNet:

-

Fine-grained recognition. We found that humans are noticeably worse at fine-grained recognition (e.g. dogs, monkeys, snakes, birds), even when they are in clear view. To understand the difficulty, consider that there are more than 120 species of dogs in the dataset. We estimate that 28 (37%) of the human errors fall into this category, while only 7 (7%) of GoogLeNet erros do.

-

Class unawareness. The annotator may sometimes be unaware of the ground truth class present as a label option. When pointed out as an ILSVRC class, it is usually clear that the label applies to the image. These errors get progressively less frequent as the annotator becomes more familiar with ILSVRC classes. Approximately 18 (24%) of the human errors fall into this category.

-

Insufficient training data. Recall that the annotator is only presented with 13 examples of a class under every category name. However, 13 images are not always enough to adequately convey the allowed class variations. For example, a brown dog can be incorrectly dismissed as a “Kelpie” if all examples of a “Kelpie” feature a dog with black coat. However, if more than 13 images were listed it would have become clear that a “Kelpie” may have a brown coat. Approximately 4 (5%) of human errors fall into this category.

Conclusions

We investigated the performance of trained human annotators on a sample of up to 1500 ILSVRC test set images. Our results indicate that a trained human annotator is capable of outperforming the best model (GoogLeNet) by approximately 1.7% (p = 0.022).

We expect that some sources of error may be relatively easily eliminated (e.g. robustness to filters, rotations, collages, effectively reasoning over multiple scales), while others may prove more elusive (e.g. identifying abstract representations of objects). On the hand, a large majority of human errors come from fine-grained categories and class unawareness. We expect that the former can be significantly reduced with fine-grained expert annotators, while the latter could be reduced with more practice and greater familiarity with ILSVRC classes.

It is clear that humans will soon only be able to outperform state of the art image classification models by use of significant effort, expertise, and time. One interesting follow-up question for future investigation is how computer-level accuracy compares with human-level accuracy on more complex image understanding tasks.

“It is clear that humans will soon only be able to outperform state of the art image classification models by use of significant effort, expertise, and time.”

As for my personal take-away from this week-long exercise, I have to say that, qualitatively, I was very impressed with the ConvNet performance. Unless the image exhibits some irregularity or tricky parts, the ConvNet confidently and robustly predicts the correct label. If you’re feeling adventurous, try out the labeling interface for yourself and draw your own conclusions. I can promise that you’ll gain interesting qualitative insights into where state-of-the-art Computer Vision works, where it fails, and how.

EDIT: additional discussions:

UPDATE:

- ImageNet workshop page now has links to many of the teams’ slides and videos.

- GoogLeNet paper on arXiv describes the details of their architecutre.

UPDATE2 (14 Feb 2015):

There have now been several reported results that surpass my 5.1% error on ImageNet. I’m astonished to see such rapid progress. At the same time, I think we should keep in mind the following:

Human accuracy is not a point. It lives on a tradeoff curve.

We trade off human effort and expertise with the error rate: I am one point on that curve with 5.1%. My labmates with almost no training and less patience are another point, with even up to 15% error. And based on some calculations that consider my exact error types and hypothesizing which ones may be easier to fix than others, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that an ensemble of very dedicated expert human labelers might push this down to 3%, with about 2% being an optimistic error rate lower bound. I know it’s not as exciting as having a single number, but it’s the right way of thinking about it. See more details in my recent Google+ post.