Feature Learning Escapades

My summer internship work at Google has turned into a CVPR 2014 Oral titled “Large-scale Video Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks” (project page). Politically correct, professional, and carefully crafted scientific exposition in the paper and during my oral presentation at CVPR last week is one thing, but I thought this blog might be a nice medium to also give a more informal and personal account of the story behind the paper and how it fits into a larger context.

Act I: Google Research Summer Internship 2011

The thread of this paper begins in Summer of 2011, when I accepted a summer internship offer from Google Research. My project involved Deep Learning for videos, as part of a great team that was at the time only a few people but would later grow to become Google Brain.

The goal of the project was to learn spatio-temporal features that could support a variety of video classification tasks. The problem, of course, is that videos are a giant 3-dimensional block of pixel values which is useless in its raw form if you’re trying to classify what objects/concepts occur within. Computer Vision researchers have come up with many ingenious ways of computing hand-crafted features over these pixels to transform the representation into one that is more directly useful to a classification task, but we were interested in learning features from raw data with Deep Learning.

” Deep Learning landscape was very different at that time. “

It’s interesting to note that the Deep Learning landscape was very different at that time. Everyone was excited primarily about Unsupervised Learning: The idea of training enormous autoencoders that gobble up all of internet data and automagically create powerful representations that support a large variety of transfer learning tasks. A lot of this ambition was motivated by:

- Human learning (people learn unsupervised, and so should our algorithms (the argument goes))

- Parallel work in academia, where resurgence of Deep Learning methods starting around 2006 has largely consisted of algorithms with a significant unsupervised learning component (RBMs, autoencoders, etc.).

- Practical considerations: unlabeled videos are much easier to obtain than labeled data - wouldn’t it be nice if we didn’t have to worry about labels?

Around this time I became particularly interested in videos because I convinced myself through various thought experiments and neuroscience papers that if unsupervised learning in visual domain was to ever work, it would involve video data. Somehow. I thought the best shot might be some kind of Deep, Slow Feature Analysis objective, but I ended up working on architectures more similar to CVPR 2011 “Learning hierarchical invariant spatio-temporal features for action recognition with independent subspace analysis”. However, the summer was over before we could get something interesting scaled over a chunk of YouTube.

Act II: Unsupervised Learnings at Stanford

I left Google that fall and joined Stanford as a PhD student. I was swayed by my project at Google and felt eager to continue working on Unsupervised Feature Learning in visual domains.

Images. One of my first rotations was with Andrew Ng, who was also at the time interested in Unsupervised Learning in images. I joined forces with his student Adam Coates who worked on doing so with simple, explicit methods (e.g. k-means). The NIPS paper Emergence of Object-Selective Features in Unsupervised Feature Learning was the result of our efforts, but I didn’t fully believe that the formulation made sense. The algorithm’s only cue for building invariance was through similarity: Things that looked similar (in L2 distance) would group together and become invariants in the layer above. That alone can’t be right, I thought.

” I couldn’t see how Unsupervised Learning based solely on images could work. “

More generally, I couldn’t see how Unsupervised Learning based solely on images could work. To an unsupervised algorithm, a patch of pixels with a face on it is exactly as exciting as a patch that contains some weird edge/corner/grass/tree noise stuff. The algorithm shouldn’t worry about the latter but it should spent extra effort worrying about the former. But you would never know this if all you had was a billion patches! It all comes down to this question: if all you have are pixels and nothing else, what distinguishes images of a face, or objects from a random bush, or a corner in the ceilings of a room? I’ll come back to this.

3D. At this point it was time for my next rotation. I felt frustrated by working with pixels and started thinking about another line of attack to unsupervised learning. A few ideas that have been dormant in my brain until then centered around the fact that we live and perceive a 3D world. Perhaps images and videos were too hard. Wouldn’t it be more natural if our unsupervised learning algorithms reasoned about 3D structures and arrangements rather than 2D grids of brightness? I felt that humans had advantage in their access to all this information during learning from stereo and structure from motion (and also Active Learning). Were we not giving our algorithms a fair chance when we throw grids of pixels at them and expect something interesting to happen?

” Were we not giving our algorithms a fair chance? “

This was also around the time when the Kinect came out, so I thought I’d give 3D a shot. I rotated with Vladlen Koltun in Graphics and later with Fei-Fei over the summer. I spent a lot of my time wrestling with Kinect, 3D data, Kinect Fusion, Point Clouds, etc. There were four challenges to learning from 3D data that I eventually discovered:

- There is no obvious/clean way to plug a neural network into 3D data.

- Reasoning about the difference between occluded / empty space is a huge pain.

- It is very hard to collect data at scale. Neural nets love data and here I was playing around with datasets on order of 100 scenes, with no ideas about how this could be possibly scale.

- I was working with fully static 3D environments. No movement, no people, no fun.

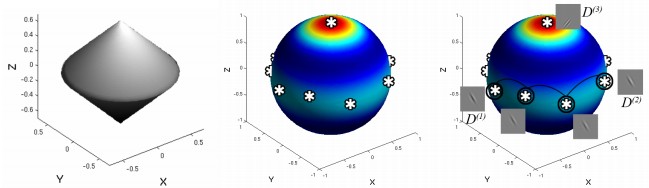

I ended up doing a bit of Unsupervised Object Discovery in my 3D meshes and publishing it at a robotics conference, where it was most relevant (Object Discovery in 3D scenes via Shape Analysis). I was happy that I found a very simple, efficient and surprisingly effective way of computing objectness over 3D meshes, but it wasn’t what I set out to do. I followed up on the project a bit while working with Sebastian Thrun for my last rotation, but I remained unsatisfied and unfulfilled. There was no brain stuff, no huge datasets to learn from, and even if it all worked, it would work on static, boring scenes.

This was a low point for me in my PhD. I kept thinking about ways of making unsupervised feature learning work, but kept coming across roadblocks– both practical but more worryingly, philosophical. I was getting a little burnt out.

Act III: Computer Vision Upside Down

Around this time I joined Fei-Fei’s lab and looked around for a research direction related to Computer Vision. I wanted my work to involve elements of deep learning and feature learning, but at this time deep learning was not a hot topic in Computer Vision. Many people were skeptical of the endeavor: Deep Learning papers had trouble getting accepted to Computer Vision conferences (see for example, famously Yann LeCun’s public letter to CVPR AC). The other issue was that I felt a little stuck and unsure about how to proceed.

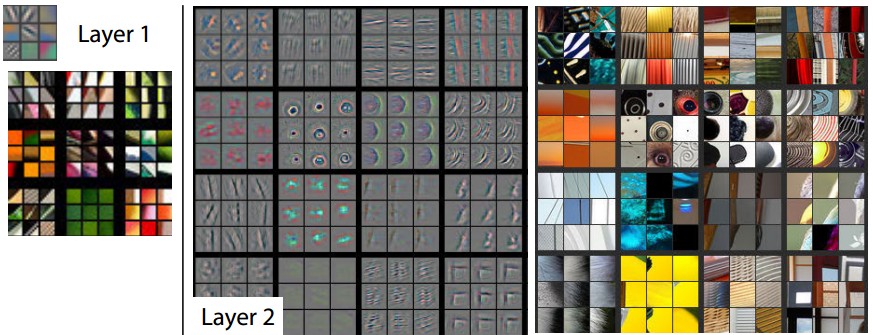

AlexNets. It was around this time that the paper that would change the course of my research, and also the course of Computer Vision came out. I’m referring to “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks”, in which a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) significantly outperformed state of the art methods on the ImageNet Classification Challenge. The described CNN architecture has become known as the “AlexNet”, after the first author of the paper: Alex Krizhevsky. ConvNets have come of age and leapfrogged from working on toy MNIST/CIFAR-10 datasets just a year ago, to suddenly running on large images and beating methods that have been developed for years. I did not expect such an astronomical leap and I think neither did most of the community.

Transfer Learning. The impressive performance of the AlexNet was interesting by itself, but the second unintuitive finding that followed was that the ImageNet-pretrained representation proved extremely potent in transfer learning tasks to other datasets. Suddenly, people were taking an ImageNet-pretrained CNN, chopping off the classifier layer on top, treating the layers immediately before as a fixed feature extractor and beating state of the art methods across many different datasets (see DeCAF, Overfeat, and Razavian et al.). I still find this rather astonishing. In some parallel universe, I can image a CNN that performs very well on ImageNet but doesn’t necessarily transfer to strange datasets of sculptures, birds and other things, and I’m nodding along and saying that that’s to be expected. But that seems to not be the universe we live in.

Fully Supervised. A crucial observation to make here is that AlexNet was trained in a fully supervised regime on the (labeled) ImageNet challenge dataset. There are no unsupervised components to be found. Where does that leave us with unsupervised learning? The main purpose of unsupervised learning was to learn powerful representations from unlabeled data, which could then be used in transfer learning settings on datasets that don’t have that many labels. But what we’re seeing instead is that training on huge, supervised datasets is successfully filling the main intended role of unsupervised learning. This suggests an alternative route to powerful, generic representations that points in the complete opposite direction: Instead of doing unsupervised learning on unlabeled data, perhaps we should train on all the supervised data we have, at the same time, with multi-task objective functions.

“… training on huge, supervised datasets is successfully filling the main intended role of unsupervised learning.”

This brings me back to my point made above: if all you have is pixels, what is the difference between an image of a face and an image of a random corner or a part of a road, or a tree? I struggled with this question for a long time and the ironic answer I’m slowly converging on is: nothing. In absence of labels, there is no difference. So unless we want our algorithms to develop powerful features for faces (and things we care about a lot) alongside powerful features for a sea of background garbage, we may have to pay in labels.

Act IV: Google Research Summer Internship 2013

When I entered Google the second time this summer, the landscape was very different than what I had seen in 2011. I left 2 years ago implementing unsupervised learning algorithms for learning spatio-temporal (video) features in baby Google Brain. Everything had a researchy feel and we were thinking carefully about loss functions, algorithms, etc. When I came back, I found people buzzing around with their engineer hats on, using adolescent Google Brain to obtain great results across many datasets with huge, 1980-style, fully supervised neural nets (similar to the AlexNet). Supervised, vanilla feed-forward Neural Nets became a hammer and everyone was eager to find all the nails and pick all the low-hanging fruit. This is the atmosphere that surrounded me when I started my second project on learning video features. The recipe was simpler. Are you interested in training nice features for X?

- Get a large amount of labeled data in X domain

- Train a very large network with supervised objective

- ???

- Profit

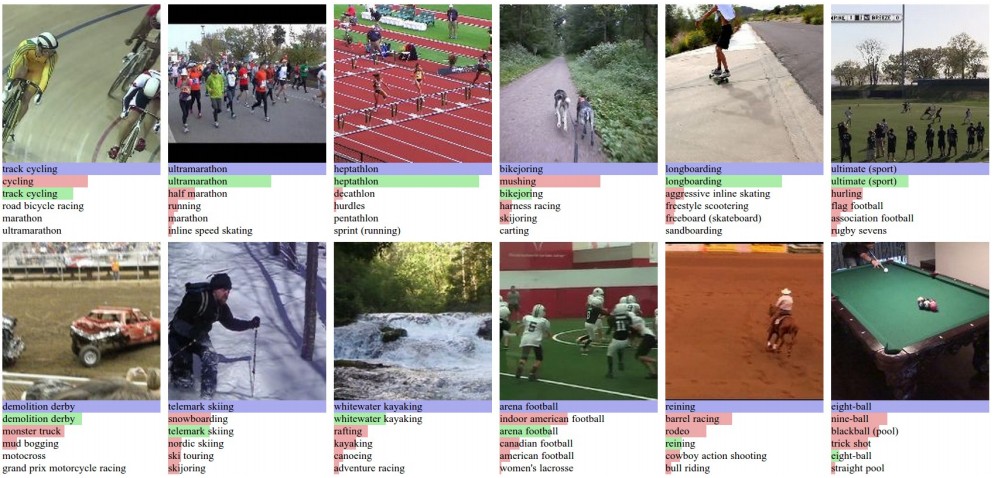

In my case, number 4 turned out to be “Large-scale Video Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks”, in which we trained large Spatio-Temporal Convolutional Neural Networks. Ironically, the dataset we chose to use (Sports videos) turned out to be a little too easy to learn rich, spatio-temporal features since the network could get very far ignoring much of the motion and relying mostly on static appearances (e.g. if you’re trying to tell difference between tennis and swimming, you need not be concerned with minute movement details). But I expect to see considerable improvements in the coming years. (From others, as I am no longer working on videos.)

Act V: Forward

Two years ago, I spent a lot of my mental efforts trying to, at least conceptually, crack the problem of learning about the visual world unsupervised. We were going to feed an algorithm with lots and lots of visual data from the internet (images, videos, 3D or whatever else), and it would automatically discover representations that would support a variety of tasks as rich as those that we humans are capable of.

But as I reflect on the last two years of my own research, my thought experiments and the trends I’m seeing emerge in current academic literature, I am beginning to suspect that this dream may never be fulfilled - at least in the form we originally intended. Large-scale supervised data (even if weakly labeled) is turning out to be a critical component of many of the most successful applications of Deep Learning. In fact, I’m seeing indications of reversal of the strategy altogether: Instead of learning powerful features with no labels, we might end up learning them from ALL the labels in huge, multi-task (and even multi-modal) networks, gobbling up as many labels as we can get our hands on. This could take form of a Convolutional Network where gradients from multiple distinct datasets flow through the same network and update shared parameters.

” Instead of learning powerful features with no labels, we might end up learning them from ALL the labels “

“But wait, humans learn unsupervised - why give up? We might just be missing something conceptually!”, I’ve heard some of my friends argue. The premise may, unfortunately be false: humans have temporally contiguous RGBD perception and take heavy advantage of Active Learning, Curriculum Learning, and Reinforcement Learning, with help from various pre-wired neural circuits. Imagine a (gruesome) experiment in which we’d sit a toddler in front of a monitor and flash random internet images at him/her for months. Would we expect them to develop the same understanding of the visual world? Because that’s what we’re currently trying to get working with computers.

The strengths, weaknesses and types of data practically available to humans and computers are fundamentally misaligned. Thus, it is unfair to draw direct comparisons and extreme caution should be taken when drawing inspiration from human learning. Perhaps one day when robotics advances to a point where we have masses of embodied robots interacting with the 3-dimensional visual world like we do, I will give unsupervised learning another shot. I suspect it will feature heavy use of temporal information and reinforcement learning. But until then, lets collect some data, train some huge, fully-supervised, multi-task, multi-modal nets and… “profit” :)